Schwartzman: Why Height Doesn't Define Me

Editor's Note:This story was first published on 24 January 2020 A lot of people ask me about my height. How does being 5’7” affect you as a tennis pro? What do you think you could have done if you were taller? My answer is always the same: I have worse problems than being 10 centimetres shorter than everybody else. When I walk onto a tennis court, I don’t think about how tall I am or how much bigger my opponent is. I know there is a difference, but so what? Maybe if I was 10 or 15 centimetres taller, I’d have a better serve or be able to hit with more power. But my height isn’t going to change. I’m not going to wake up the size of John Isner or Ivo Karlovic. There are reasons that I might not have made it here, but they have nothing to do with my size. Before I was born, my family earned an amazing living in South America. They owned a clothing and jewelry company that made them a lot of money. They had a house in Uruguay where they went every December and January to enjoy the summer. They had a house in the capital and another one outside the capital. They owned many cars. Life was amazing. But things changed when I was born. My family lost everything. In the 1990s in Argentina, the government cut imports. My father kept spending money to try to get things from outside the country, but there was no chance and he started doing worse and worse and worse. It was terrible. My mom tried to get the material for clothes from China, but there was no way to get it in Argentina. My family had no more business, no more extra houses and cars. Just me, my two older brothers, my older sister and my parents trying to make a living for us. Because we didn’t have a lot of money, it was really tough to start playing tennis or any sport for that matter. We really couldn’t afford it. But I played as much as I could. I was actually named after football legend Diego Maradona, so of course one of the sports I played was football. When I was little, my grandmother bought me uniforms from European teams like Real Madrid and Barcelona. The first team I played for, I scored a lot. I would go to the club to try tennis, too, wearing those same jerseys my grandmother got me. If the courts were full, I would play in a hallway with my father. We always used adult racquets even if I was little, because I never liked the kids racquets. As the years went by, I realised that in tennis, most things depended on me, and not others around me. It would be about the effort I put in, and there was a charm about knowing I would be rewarded for the work I put in. I also was better at tennis than football, so I wanted to take it more seriously. I started travelling to many tournaments with my mother. My dad would promise me that he booked us a nice hotel with TV, computer, Internet and everything that we needed. Why are you lying? I used to call him all the time to ask that. There was never a TV, and at almost every tournament we went to we had to share one bed. We stayed once at a hotel because a room cost only two pesos. It was the same thing over and over, but we had no choice. This is what we could afford. At one point, we were even selling rubber bracelets that were left over from the business my family had. We did anything we could do to get money to pay for trips to tournaments and the travel costs. Looking back, it was a tough situation. But at the time, it was funny. I helped my mom selling the bracelets, and so did some of the other players. Between matches we would all run around with a bag of bracelets to see who could sell the most, and my mom would give them 20 per cent of the money. It was like two competitions in one — tennis and selling bracelets! [MY POINT] I sort of understood at the time why we did all this, but I didn’t feel it, because my parents were trying to work hard to let me focus on playing and travelling while they worried about the money. When I was 13, I began to go on flights by myself to places like Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador, and I would cry on the plane. I wanted to be with my family. But playing those events was part of my journey. And I know that even if those times were difficult, they helped me become a better competitor. Also, when I was 13, a doctor told me I would never be taller than 5’7”. I know I told you that height doesn’t mean much. But back then, I was devastated. I didn’t know what I was going to be able to do well with my life if the doctor was right. I didn’t know if I still wanted to play tennis. My parents didn’t let me get down, though. They told me my height shouldn’t influence my dreams. And luckily, when I was 15 or 16, I started to have many people around who tried to help me with money, travel, a coach, a trainer, with everything. At that point, it became easier for my family and me. I was never a top junior — the only junior Grand Slam I played was the 2010 US Open qualifying, where I lost in the first round. I messaged my family that day that I didn’t know what I was doing there.

Editor's Note:This story was first published on 24 January 2020

A lot of people ask me about my height.

How does being 5’7” affect you as a tennis pro? What do you think you could have done if you were taller?

My answer is always the same: I have worse problems than being 10 centimetres shorter than everybody else.

When I walk onto a tennis court, I don’t think about how tall I am or how much bigger my opponent is. I know there is a difference, but so what?

Maybe if I was 10 or 15 centimetres taller, I’d have a better serve or be able to hit with more power. But my height isn’t going to change. I’m not going to wake up the size of John Isner or Ivo Karlovic.

There are reasons that I might not have made it here, but they have nothing to do with my size.

Before I was born, my family earned an amazing living in South America. They owned a clothing and jewelry company that made them a lot of money. They had a house in Uruguay where they went every December and January to enjoy the summer. They had a house in the capital and another one outside the capital. They owned many cars. Life was amazing.

But things changed when I was born. My family lost everything. In the 1990s in Argentina, the government cut imports. My father kept spending money to try to get things from outside the country, but there was no chance and he started doing worse and worse and worse. It was terrible. My mom tried to get the material for clothes from China, but there was no way to get it in Argentina.

My family had no more business, no more extra houses and cars. Just me, my two older brothers, my older sister and my parents trying to make a living for us.

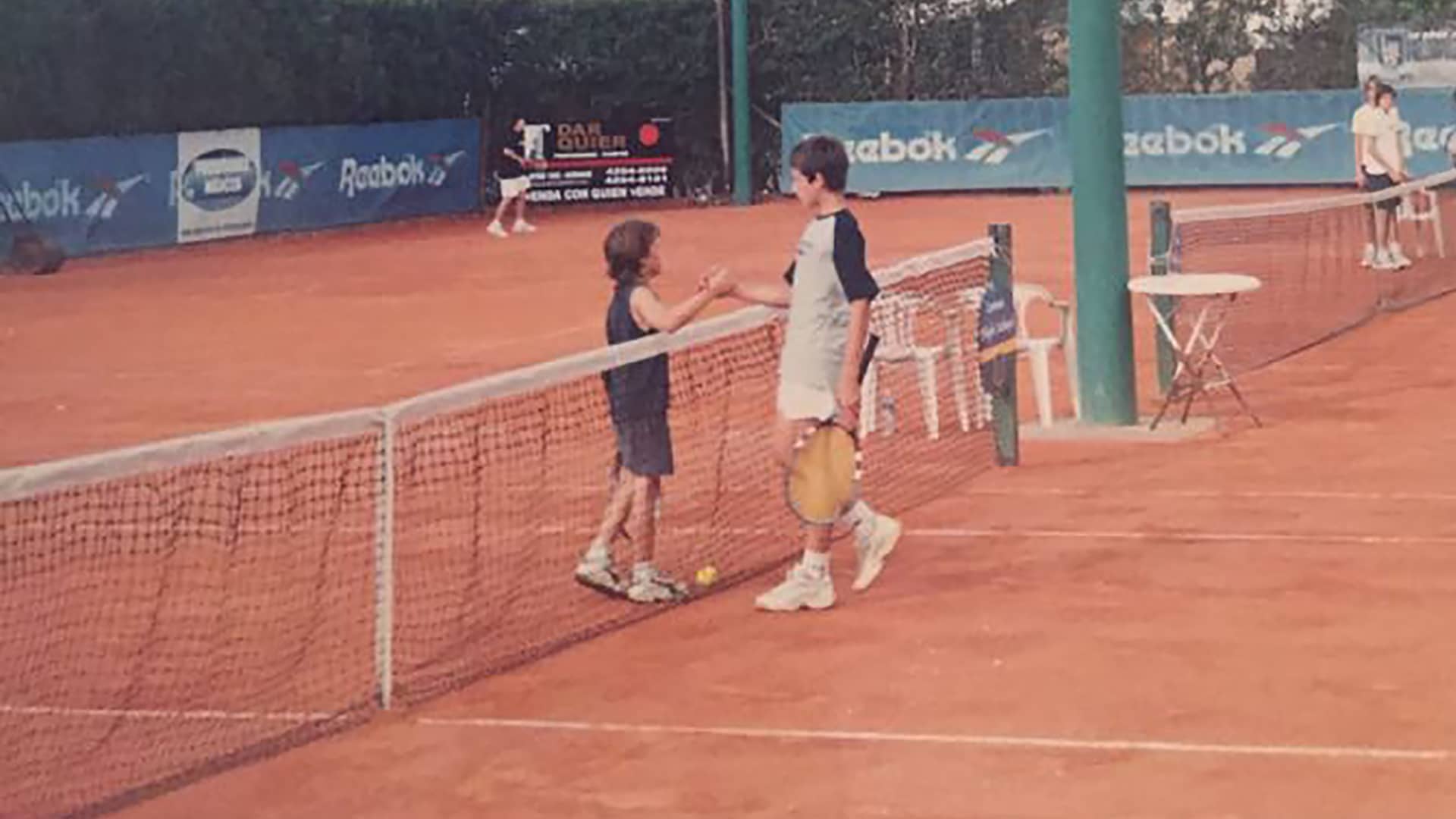

Because we didn’t have a lot of money, it was really tough to start playing tennis or any sport for that matter. We really couldn’t afford it. But I played as much as I could.

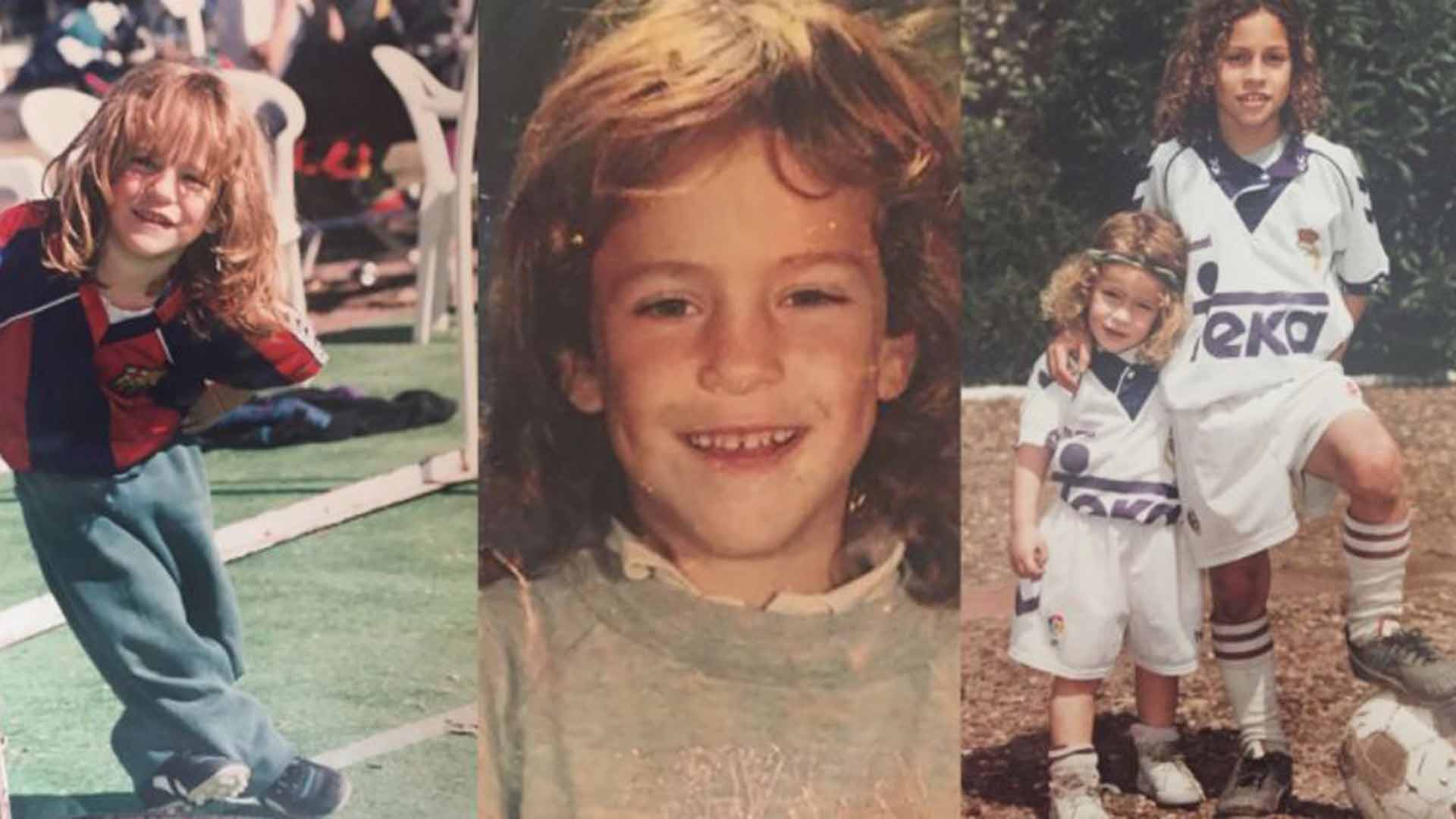

I was actually named after football legend Diego Maradona, so of course one of the sports I played was football. When I was little, my grandmother bought me uniforms from European teams like Real Madrid and Barcelona. The first team I played for, I scored a lot. I would go to the club to try tennis, too, wearing those same jerseys my grandmother got me. If the courts were full, I would play in a hallway with my father. We always used adult racquets even if I was little, because I never liked the kids racquets.

As the years went by, I realised that in tennis, most things depended on me, and not others around me. It would be about the effort I put in, and there was a charm about knowing I would be rewarded for the work I put in. I also was better at tennis than football, so I wanted to take it more seriously.

I started travelling to many tournaments with my mother. My dad would promise me that he booked us a nice hotel with TV, computer, Internet and everything that we needed.

Why are you lying?

I used to call him all the time to ask that. There was never a TV, and at almost every tournament we went to we had to share one bed. We stayed once at a hotel because a room cost only two pesos.

It was the same thing over and over, but we had no choice. This is what we could afford.

At one point, we were even selling rubber bracelets that were left over from the business my family had. We did anything we could do to get money to pay for trips to tournaments and the travel costs.

Looking back, it was a tough situation. But at the time, it was funny. I helped my mom selling the bracelets, and so did some of the other players. Between matches we would all run around with a bag of bracelets to see who could sell the most, and my mom would give them 20 per cent of the money. It was like two competitions in one — tennis and selling bracelets!

[MY POINT]I sort of understood at the time why we did all this, but I didn’t feel it, because my parents were trying to work hard to let me focus on playing and travelling while they worried about the money.

When I was 13, I began to go on flights by myself to places like Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador, and I would cry on the plane. I wanted to be with my family. But playing those events was part of my journey. And I know that even if those times were difficult, they helped me become a better competitor.

Also, when I was 13, a doctor told me I would never be taller than 5’7”. I know I told you that height doesn’t mean much. But back then, I was devastated. I didn’t know what I was going to be able to do well with my life if the doctor was right. I didn’t know if I still wanted to play tennis.

My parents didn’t let me get down, though. They told me my height shouldn’t influence my dreams. And luckily, when I was 15 or 16, I started to have many people around who tried to help me with money, travel, a coach, a trainer, with everything. At that point, it became easier for my family and me.

I was never a top junior — the only junior Grand Slam I played was the 2010 US Open qualifying, where I lost in the first round. I messaged my family that day that I didn’t know what I was doing there. But I don’t think about all of those tough times much anymore. And once I became a professional, I never doubted myself, no matter the odds.

I always had confidence in my game and my career. I always thought I could do it. Here I am now, competing with the best players in the world.

Knowing what my family went through taught me valuable lessons about the importance of family, and gave me a better understanding of how to look at the bigger picture when it comes to sports. Whatever happens in my career doesn't compare to what my parents endured.

But even all of that pales into comparison to what my ancestors went through. I have Jewish roots, and my great grandfather on my mom’s side, who lived in Poland, was put on a train to a concentration camp during the Holocaust.

The coupling that connected two of the train’s cars somehow broke. Part of the train kept going, and the other stayed behind. That allowed everyone trapped inside, including my great grandfather, to run for their lives. Luckily, he made it without being caught. Just thinking about it makes me realise how lives can change in a heartbeat.

My great grandfather brought his family by boat to Argentina. When they arrived, they spoke Yiddish and no Spanish. My father’s family was from Russia, and they also went to Argentina by boat. It wasn’t easy for all of them to totally change their lives after the war, but they did.

So from my ancestor escaping a train on its way to a concentration camp to staying in tiny hotel rooms and selling bracelets, I consider myself lucky. But everyone has a story. I’m not the only one who has faced adversity. It’s about not letting the tough moments drag you down, and using them as motivation to help you turn a bad situation into something good.

I never imagined my career being where it is now. But no matter what I’ve dealt with, I’ve always worked hard, and I think pushing through those hurdles has made me a better competitor and an even better person. If I can get this far, so can you. Believe in yourself no matter what, give everything you have and one day — even if you’re 5’7” — you can accomplish your dreams too.

Read More 'My Point' First-Person Essays

- As told to Andrew Eichenholz, with reporting from Juan Diego Ramirez Carvajal and Marcos Zugasti.

Admin

Admin